A few days ago Dan Counsell wrote about using a more frequent release schedule, a practice I’ve seen many developers switching to and which can help with limiting user backlash (while some users love shiny new updates, others hate them and will use one-star App Store reviews to let you know).

It’s definitely tempting to want to bundle more and more into a single update (a practice I’m guilty of at times), but there’s one additional benefit of frequent updates Dan didn’t address: it creates the perception of a well-maintained app. With 65% of iOS apps considered abandoned1 and App Store search broken, the App Store has essentially become a junkyard filled with incredible amounts of garbage and only the increasingly rare gem of a find. So when someone manages to actually find your app card, don’t lose them on something you can control. As a consumer, one of the best indicators of an app’s health is the date of its last update. Limiting the scope of an update and splitting its goals into several smaller, incremental updates achieves this. It’s unfortunate, but an updated date more than six months old is often a sign that the app has been abandoned, and potential purchasers are usually smart to save their money.

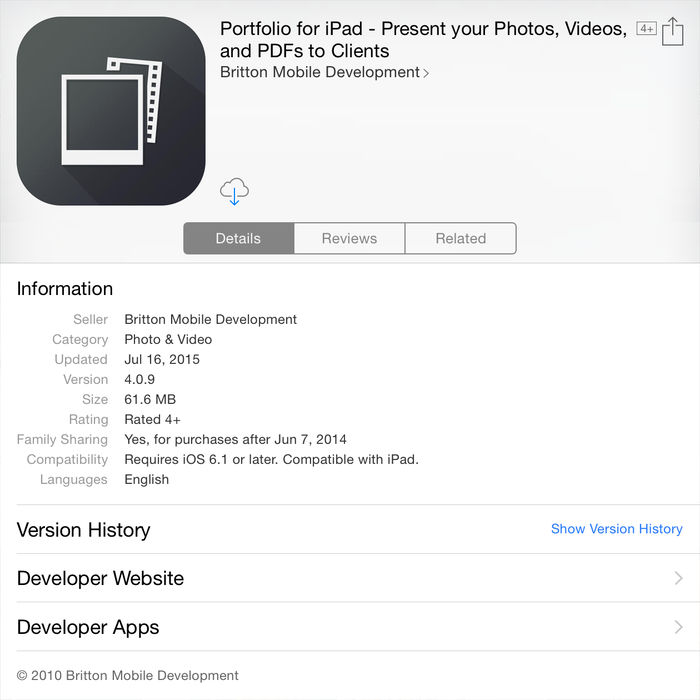

All of that said, a large update can still have its place. At the beginning of the year I released Portfolio 4.0, a relatively large update. This update would have been impractical to do as a series of smaller updates – the things it addressed included bits of technical debt that needed to be handled completely or skipped entirely as well as an appearance refresh and overhaul.

Part of Portfolio’s technical debt involved switching the codebase over to ARC. I had held off on ARC at first because of the very brief lifetime Garbage Collection had. As the app evolved and ARC looked like it was here to stay, new additions to the codebase had been mostly written with that kind of memory management rather than manual memory management. Older code, however, had not been updated to do the same, and I felt it was becoming increasingly risky to keep the two methods both in use.

Any app spanning multiple iOS versions will also accumulate a significant amount of version checking cruft. Behaviors that change with the introduction of new iOS features need to be checked for, and doing so usually requires injecting a bunch of conditional statements whose only purpose is to perform one action on iOS x – 1 and another on iOS x. When support for older versions gets dropped, these often get left in place since they don’t generally affect anything other than the legibility of the code. After five years they definitely add up.

iOS 7 introduced the now-standard flat appearance. Such a radical departure from previous appearance standards meant a significant amount of work to rethink and redesign the interface while keeping it familiar enough for existing users. Up until Portfolio 4.0 I had only done a superficial job of updating the appearance, and I felt that this point, slightly more than a year since iOS 7, was definitely time to do it. Its metaphors and methods of interactions needed to look like they were made along side the flat appearance and not taped on.

Each of these alone involved touching nearly every source code file in the app. Rather than doing them separately and revisit the files multiple times, I thought it best to not drag out the updates and do it all at once. Even in hindsight I still feel this was the correct decision.

Going forward, I will likely stick solely to smaller updates. It’s easier to maintain, and it also makes addressing user requests and problems in a timely manner easier (I’ve never been a big fan of dealing with source control merges on single-person projects). Portfolio 5.0, whenever that happens, will not be as substantial of an update as each of its predecessors.

- This infographic is based on 2013 data. No newer one has been released that I’ve been able to find. ↩