As I write this, we’re hours away from setting off for Ketchum, ID to ride Sun Valley Resort. We’ve packed nothing, the truck still needs fueled, the propane needs refilled, and I need to dewinterize the trailer. If nothing else, this trip has shown exactly why winter camping requires the flexibility it does. Between yesterday’s heavy snow and today’s 60 mph wind, we’re setting off at least two days later than we initially aimed for.

Winter RVing in the mountains is impossible to plan for much in advance when forecasts change by the hour. One day’s time in a forecast can mean driving through a blizzard rather than in sun and on dry pavement, and it requires as much flexibility in departure and arrival times as in where you actually stay the night. During the winter, you’re often operating at or beyond the edge of what these units are designed for.

We didn’t end up leaving until a full week after starting writing thanks to road and pass closures.

The Destination

Traveling with an RV is not cheap, even less so during the winter where in addition to engine fuel costs you also have propane and sometimes generator gas. The trade is one of cost savings elsewhere (mountain lodging and food is expensive) and the convenience of location, sometimes at the base of the slopes. We do it because it enables us to follow the snow without having to worry as much about the typical month-long cancelation window of a mountain hotel. Choosing the destination then is more an exercise in logistics:

- Which is the best winter route? Most places you’ll end up going have more than one route to get there. Problem is, the most direct route is rarely the best maintained during the winter if even open at all. Chinook Pass on WA 410 is one such example — what would be a four-hour drive for us to reach Crystal Mountain Resort is six or more hours during the winter due to that pass being closed.

- Is there somewhere to park? Some mountains provide dedicated parking areas while others may have an open campground nearby.

- Is there a power hookup? Winter means the furnace will be running, which means either shore power or a daily generator run. We choose not to use indoor portable propane or electric heaters because of possible safety issues and they don’t adequately heat the belly where the tanks are.

- How long are you going? Conservatively, our propane can heat our trailer for about a week or two before needing refilled. The colder and windier it is, the shorter that window can get.

- And most importantly, can you even get there? Many passable highways during temperate times of year can be restricted or completely closed during the winter (temporarily due to avalanche danger or for the entire season). Teton Pass on WY 22 prohibits trailers during the winter, for example, making Jackson Hole impractical to visit by RV for us.

The Route

For this trip, our destination is Sun Valley Resort in southern Idaho. The most direct route is east to Missoula, MT and straight down US 93/ID 75, but that route is much less ideal in the winter. Instead, we’re better off taking the interstates as much as possible despite nearly 100 miles more distance each way (or, as I count it, most of a tank of gas).

In general, the roads most traveled are the ones highest on the winter maintenance list, but the region also plays a big part in it. An area that regularly experiences severe winter weather like Whitefish, MT is going to be much more prepared than one that doesn’t — coastal ski areas are a notable example of this where snow rarely falls at the lower elevation of the main roads in, and their plow fleet reflects it.

Tires on bare pavement or dirt or gravel makes up most of a normal camping season. In the winter, you get to add a few more surfaces to that list, all various forms of snow and ice. With towables it’s very common for the trailer to weigh more than the tow vehicle (almost 2000 lbs more for us), so traction becomes very, very important. Legally in most mountainous states this means carrying chains, but those are also practical as well and can mean the difference between waiting something out stuck in place or slowly making your way to better conditions. We carry enough chains to satisfy the most stringent requirements (Washington’s) in addition to cat litter and deicer for a quick patch of gravel.

WAC 204-24-050

Use of tire chains or other traction devices.

…

(2) Vehicles or combinations of vehicles over 10,000 pounds gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR).

When traffic control signs marked “chains required” are posted by the department of transportation it will be unlawful for any vehicle or combination of vehicles to enter the controlled area without having mounted on its tires, tire chains as follows: Provided, That highway maintenance vehicles operated by the department of transportation for the purpose of snow removal and its ancillary functions are exempt from the following requirements if such vehicle has sanding capability in front of the drive tires.

(a) Vehicles or vehicle combinations with two to four axles including but not limited to trucks, truck-tractors, buses and school buses: For vehicles with a single drive axle, one tire on each side of the drive axle must be chained. For vehicles with dual drive axles, one tire on each side of one of the drive axles must be chained. For vehicle combinations including trailers or semi-trailers; one tire on the last axle of the last trailer or semi-trailer, must be chained. If the trailer or semi-trailer has tandem rear axles, the chained tire may be on either of the last two axles.

…

(f) All vehicles over 10,000 pounds gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) must carry a minimum of two extra chains for use in the event that road conditions require the use of more chains or in the event that chains in use are broken or otherwise made useless.

(g) Approved chains for vehicles over 10,000 pounds gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) must have at least two side chains to which are attached sufficient cross chains of hardened metal so that at least one cross chain is in contact with the road surface at all times. Plastic chains will not be allowed.

Translation: towing an RV in Washington requires carrying a total of five chains. One is required for one wheel of the trailer, two for one drive axle of the truck, and a spare pair for the truck (Oregon requires chaining the whole axle of the trailer, so that second trailer chain isn’t wasted).

Parking

The number of ski resorts that offer parking is relatively small given the number of resorts across the western half of North America. In our case for this trip, Sun Valley does not have winter RV parking within the resort itself; the nearest open RV park is in Ketchum and offers full hookups. Generally, the less resorty the resort, the easier and cheaper parking at the resort will be. Few if any resorts with lodging will offer RV parking for obvious reasons.

Power

Having a power hookup cannot be valued highly enough in the winter. Without it, the furnace is a constant concern due to its power draw of up to 150W for the fan blower motor, and you can easily use everything in a typical dealer-provided battery bank by morning. The furnace is the reason why I upgraded batteries last year since having enough power to run it all night is slightly important.

Flooded lead acid batteries must be stored where they can vent, which means they’re exposed to the outside environment. Because of this, it creates two additional problems while boondocking in the winter: cold reduces the available capacity and as a battery depletes, its freezing point rises. Winter temperatures can easily cut the usable battery capacity in half, which means a daily generator run is virtually guaranteed.

Assuming a typical nighttime winter alpine temperature of around 10°F, the power draw from the furnace will be around 800-900W, which works out to roughly 70 amps. Factoring in the 50% capacity drop due to the temperature and the 50% depth of discharge safety margin, this means a battery bank of at least 280 Ah is needed for the best battery life. The dual-12V marine batteries usually included with an RV are less than half of that.

Boondocking in the winter needs either internally-stored batteries (e.g., lithium, AGM, gel, or similar) or a large FLA battery bank. Anything else may be a very, very cold night.

Length of Trip

While most RVs sit winterized in storage from November until April, those of us that ski and snowboard try to use them through the winter, and the best destinations for us also mean the worst driving conditions. This can mean delays in leaving for a trip or extending a trip due to weather, maybe due to waist-deep powder that’s worth another lift ticket or road conditions on the way out that have you stuck in place. Either way, it means overstocking supplies to make it through — it’s not a good time of year to be forced onto the road because you’re out of something critical.

Food can generally be purchased at the resort in the event you run out, and water can usually be obtained somewhere close. What can’t be is heat, especially the propane variety. An electric heater is a good final contingency to carry, but unwinterized RVs require the furnace to run in order to keep the tanks and lower plumbing thawed, and that takes propane.

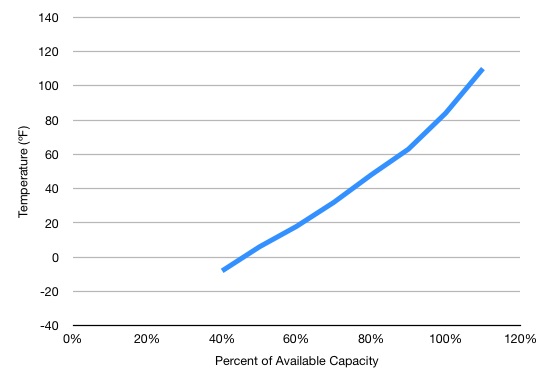

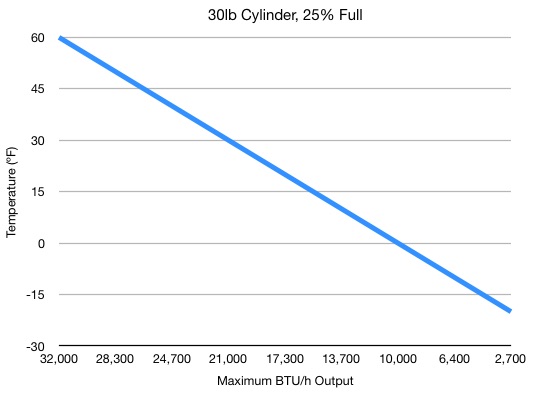

Most winter-ready RVs carry two 30 lb tanks of propane, which I find lasts around a week combined or slightly more during skiable weather. Unfortunately, the colder it is, the shorter the time it lasts. It’s also compounded by propane providing fewer BTUs per hour as the temperature drops — between 20°F and 0°F, a 30 lb tank of propane provides up to 42% less output as the tank gets close to empty. If it drops lower than the rate it’s being consumed, it can cause the related appliances to shut off.

While I try to monitor the propane level fairly closely, I carry an extra 20 lb tank as an emergency backup. Worst case, it will provide an extra day or two of heat and gives me a chance to refill the main tanks, but longer term I plan to carry the supplies necessary to rewinterize the trailer on the road.

At around 0°F, I see 1-2% of a tank consumed per hour in our trailer. Wind increases that. Because of the fast burn rate, I strongly suggest a remote capacity monitor.

Other Winter Considerations

Beyond the logistics of planning the trip, there are other factors that can complicate a trip, almost all of which are weather-related.

Refrigerator

RV refrigerators operate nothing like residential ones. Instead of a compressor, they have an ammonia boiler, which allows it to run off any sufficient heat source (electric or propane being the two of choice). Under normal conditions, the boiler converts the ammonia-water mixture into vapor, which rises up to the point where the water portion re-condenses leaving the ammonia vapor to continue on to the cooling section. When overly cold out, the ammonia condenses too early and prevents much, if any, of the ammonia vapor from reaching the cooling section.

Our trailer is equipped with what Norcold calls the cold weather package, which is an electric-powered auxiliary heating strip. This allows the fridge/freezer to function down to 0°F, though with one exception: wind penetrating into the cooling stack can negate the gain from the heating strip resulting in no cooling (I’ve seen this happen as high as 15°F). The only solution to this is to increase the temperature of the cooling stack’s compartment, which can be done by temporarily blocking off one end of the cooling stack’s venting to prevent wind from over-cooling it and/or adding another heat source (e.g., an incandescent light bulb). Neither are ideal due to the fire risk if forgotten once warmer weather comes, but it can be the only option.

Too Cold for Propane

Fortunately for RV skiing, this one is not usually a major concern, but it is within the realm of possibility. For a propane system to function, the liquid propane in a tank must be able to convert into a gas, which happens at any temperature above -44°F. If at or below that, propane will not flow to the appliances that want it, and the only solution is auxiliary heating or moving somewhere warmer. Tank warmers exist and are something I’d like to investigate, if for no other reason than to mitigate some of the BTU/h drop due to the cold.

Humidity

One of the most common complaints of winter RVing in general is condensation, which is caused by high relative humidity inside and cold temperatures outside. Add in wet gear from snowboarding and skiing, and the humidity level inside can increase quickly. Left alone, it can saturate upholstery and create ice sheets on the inside walls, all of which can eventually lead to rot and mold.

Air circulation is important, but for the humidity levels the wet gear can bring, it alone isn’t enough. Humidity removal is easily handled by using a dehumidifier, which come in two main types: cold plate and compressor. The small countertop ones that should be perfect for an RV are the cold plate variety, but they don’t work well enough to make a difference. Desiccants are also similarly ineffective. The compressor-based dehumidifiers are the only option I’ve found effective.

If boondocking, I have found it sufficient to only run the dehumidifier during generator run periods. The humidity is high in the morning, but it’s quick to get under control.

Water and Dumping

Many RV parks, even if open during the winter, do not have the liquid-based hookups fully operational. We always carry a full tank of water and try for only a single tank dump if at all possible. This, of course, means the furnace needs to run regularly in order for the tanks to stay thawed. We do not ever run an electric heater while dewinterized, though we do carry one in case of an absolute emergency.

Frozen to the Ground

We use a variety of blocks for leveling out the trailer and to provide a solid surface for the stabilizers. Where these meet the ground they often freeze to it, making for a challenging time breaking camp. Our “winter kit” of these now is just an assortment of scrap wood because sometimes it requires a hammer to get them unstuck, and the normal plastic ones become very brittle in the cold (we have a few with chunks missing now).

When the hammer and shovel fail, such as when the power cord becomes buried in snow that later solidifies, the best trick I’ve found is a mixing bowl from the trailer and hot water from the outside shower. Depending on the depth it’s embedded it can take several bowls, but it does eventually work.

Final Thoughts

When we were first seriously looking at trailers, the one question I could never get an answer to was how cold could it handle? I don’t necessarily think this was due to avoiding committing to a value but more because, despite often being RVers themselves, those at dealerships typically use them in the normal months like most everyone else. They can’t answer because they don’t know.

We have enough experience now with outings in virtually all weather that I feel I can reasonably answer it. Winter capabilities vary wildly between different makes of RVs, so while the above post is generally applicable across the board, the following may not be. My experience using an Outdoors RV trailer in all four seasons can be covered in the following breakdown:

Temperature: 90°F +

- The single air conditioner may not be able to keep up and may run all of the time. There is a factory option for a second (plus 50 amp power panel), which can be a good decision if planning to use regularly in hot areas.

- RV fridges may have trouble cooling and need auxiliary fans to push more air across the condenser.

Temperature: 70-89°F

- The air conditioner may be needed but will not run overly often.

- Not ideal for boondocking if AC is wanted due to its power draw.

- This temperature range will likely have no issues that need any extra effort.

Temperature: 40-69°F

- Unlikely to use air conditioner at all, so virtually everything needed can be run solely off DC power, which is great for boondocking.

- Furnace will be needed but will not run frequently, so the power draw can easily be made up via solar or infrequent generator use.

- No risk of freezing, so electric heat may be desirable if on shore power to save on propane. I’d estimate a month or more from the two tanks even if using the furnace.

- May need humidity removal on the lower end of the range if exceptionally humid outside but generally unlikely.

Temperature: 20-39°F

- Easy winter camping, but this is where you’ll start to discover every ingress of cold outside air. I’d definitely recommend addressing them before venturing into anything colder.

- The furnace is needed, but the propane will probably last 2-3 weeks at the frequency it runs.

- Humidity can start to become an issue as it condenses to the windows, frames, and some walls.

- It can snow from the temperature down, so having some ability to remove it from the roof for travel is necessary.

Temperature: 10-19°F

- Cold air penetrations need to be fixed by this point. Additional insulation can also help, such as between the pass-through storage and bedroom (there is none — just an air gap).

- Airflow and humidity removal become very important as just a night of breathing can add 30%. Two common airflow dead zones that need addressed are below the mattress and behind the dinette where the cushions touch the outside wall. See my post on winter camping upgrades for more details.

- Propane usage becomes a monitoring concern, offering as little as 1-2 weeks of running time. I like to carry a spare smaller tank that can buy some time if I somehow run out with the main tanks.

- The fridge’s cooling may become an issue if windy because it will interfere with the ammonia condensing process.

Temperature: 0-10°F

- Very much like the previous temperature range but more on the edge.

- The furnace can easily run 40 minutes out of every hour during the night, which uses a ton of propane. Don’t expect more than a week out of the two main tanks.

- 0°F is the theoretical operating limit of Norcold refrigerators with the cold weather package — it has successfully worked for us, both on electric and propane.

Temperature: -10-0°F

- This is the coldest we’ve been in. It was not much different from the previous temperature range except that condensation freezes to window frames almost immediately. It’s important to keep up on, but it actually increases at a slower rate because there’s typically less moisture in the air outside.

- Propane usage can easily cause running time to drop below a week.

Wind

Wind exacerbates all of the above concerns. If it’s windy, you can basically treat the wind chill temperature as the operating temperature because that’s what the furnace and fridge will run like. Skirting is usually the only effective mitigation to the wind-induced issues.